Black ex-coach, graduate detail racial incidents in Fort Dodge School district, call for equity

Two years after an errant text, racial incidents and his firing, a Black ex-coach wants his job back — and systemic change

Editor’s note: This story has been reported multiple times on Facebook and has been removed there. Hoping you’ll read and share it here. 🖤

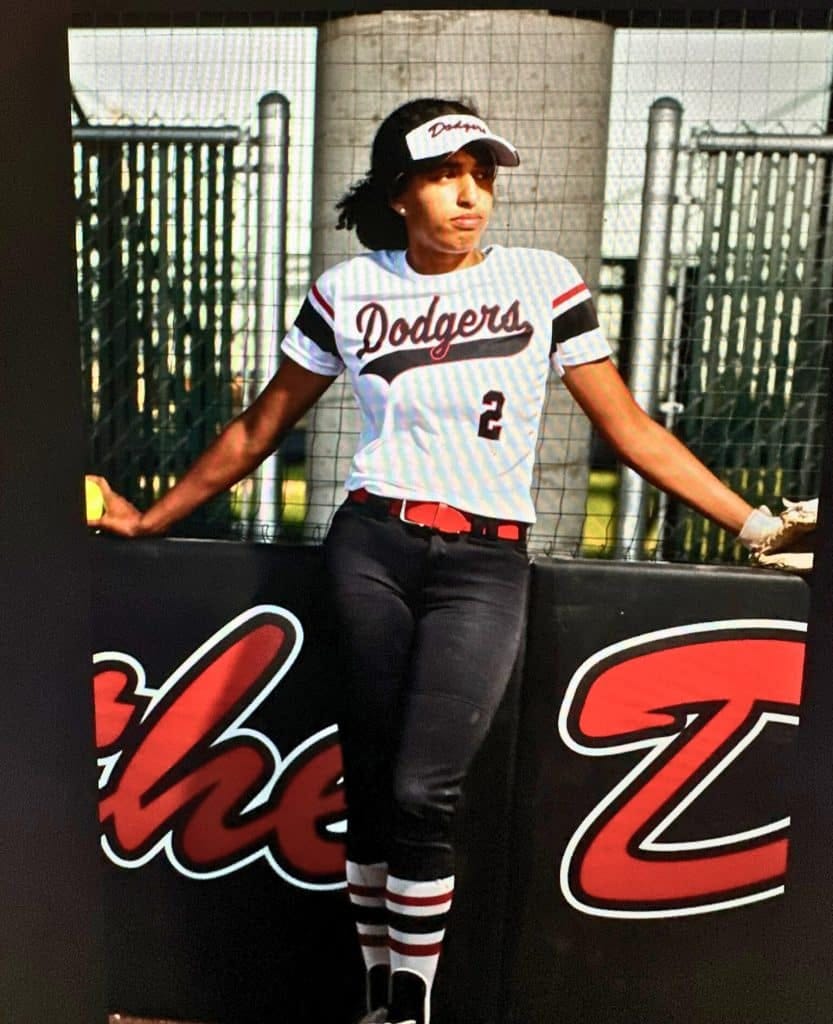

As Quennel McCaleb prepared for bed, he thought about the local newspaper’s sports coverage. The proud dad and coach for the Fort Dodge Community School District hoped his then 15-year-old daughter, Meah, a freshman athlete, would make the sports section.

But in an interview with Black Iowa News, he said he felt the sport’s coverage was biased in favor of the daughter of his colleague, head softball coach Andi Adams, Meah’s coach. McCaleb, 44, grabbed his iPhone and sent a slang-laden text to his wife, who typically picked up the newspaper on her way home from the night shift as a nurse.

“Is Meah name in the paper? Eric (the reporter) riding Jalen d**k so hard. Did Meah name get brought up,” stated the text he sent at 11:28 p.m. on June 21, 2022.

But it wasn’t a text to his wife, Lacey. Instead, McCaleb, then a head varsity track coach, head 7th-grade football coach and student support services liaison, had inadvertently sent the text to the softball parents’ text group.

Immediately, his wife called him upset. He tried to explain, blaming the sleeping pill and pain meds he’d taken to dull the pain from a recent surgery. He apologized to her and everyone in the text group, he said: “I didn’t mean it to come across like that . . . it came out like vomit.”

“In our culture, when we say d**kriding, that means riding coattails or brown-nosing,” McCaleb told Black Iowa News.

According to the Urban Dictionary, “d**kriding” is when someone overpraises another person with intentions to get noticed or approval or acts like a groupie. The slang is common in Black sports talk and rap.

“It’s tragic that the community don’t know the truth,” said McCaleb, an at-large member of the Fort Dodge City Council. “It has no sexual meaning behind it.”

McCaleb said the text controversy fueled gossip and rumors, caused tension and diverted attention from the source of the problems – routine racial discrimination. Javion Jondle, a former Fort Dodge high school football captain, said repeated Black jokes and racial incidents involving white coaches and teammates severely harmed his mental health and took a toll on him. His mother, Andrea Jondle, who documented her son’s struggles on Facebook, dubbed #JohnnyChronicles, said one of her son’s white coaches tried to silence her for the social media posts.

“There is nothing but racism ingrained into that school district,” McCaleb said.

‘Racism ingrained into that school district’

The fallout from the text, McCaleb said, culminated in a written warning from the district on June 29, 2022, “relating to a text message you sent to the softball parent text group where you made disparaging remarks about another student.” McCaleb’s Oct. 17, 2022, termination letter cited several social media posts “related to your employment in a manner that is disparaging to other employees and disruptive to district operations” and other reasons he was fired. McCaleb claims the district used the errant text as a “pretext” to fire him for continuing to advocate for himself, his daughter and minority students and staff who had alleged racial discrimination.

In the Iowa Civil Rights Commission (ICRC) complaint he filed on May 12, 2023, and cross-filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), McCaleb named the district and the following school employees:

Staci Laird, Fort Dodge Senior High School principal

Josh Porter, assistant superintendent and former athletic director

Andi Adams, teacher and softball coach

Dan Adams, football coach

Nik Moser, head football coach

Kirsten Doebel, former director of secondary education

Kimberly Whitmore, director of human resources

Porter and Doebel declined to comment. Moser, Whitmore, and Laird didn’t return calls or emails seeking comment.

The Adamses and Moser were labeled in the civil rights complaint as the “good ol’ boys,” and McCaleb said he repeatedly reported them to Laird for alleged “racial comments and activity.” He also alleged in the complaint he was unjustly harassed and retaliated against due to his race and disability status.

In response to Black Iowa News’ repeated requests for comment from the district and named employees, Fort Dodge Schools Communications Director Lydia Schuur emailed, “FDCSD administration is new, and while they are working on goals and initiatives, they do not have anything to comment on at this time.”

Schurr didn’t provide details about the goals and initiatives.

The district repeatedly cited personnel and privacy concerns as reasons it couldn’t provide information about McCaleb’s complaints or respond to McCaleb’s allegations of racism, discrimination and retaliation against Black coaches and Black student-athletes. In the district of 3,423 students, about 7 percent are Black, according to the Iowa Department of Education.

“Complaints involving students and employees are confidential under Iowa Code section 22.7 7 and FERPA,” the district emailed. “The district cannot provide this information.”

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) is a federal law that protects the privacy of student education records and applies to all schools that receive funds under an applicable program of the U.S. Department of Education.

McCaleb, who worked in a variety of roles in the district from 2020-2022, alleges his daughter, now a rising senior, has faced ongoing retaliation while playing for Andi Adams. He alleged Meah has repeatedly been excluded from some team activities and the injuries Meah sustained while playing weren’t properly handled by Andi Adams.

“When I got fired, they started targeting her,” McCaleb said.

Andi Adams has denied allegations of racism.

“There’s definitely not any of that going on because she’s playing with me,” said Adams, of Meah, before referring further questions to district officials.

McCaleb’s complaints haven’t gone the way he’d hoped, but he’s still seeking redress for his claims.

The commission, which acts as a neutral fact-finder, administratively closed his complaint without investigation on Aug. 2, 2023, and denied a request to reopen it on Nov. 1, 2023. The ICRC’s Summary Order and Notice Denying Reopening addressed several issues, among those:

Harassment: The district “provided evidence that it acted on the complaints” McCaleb raised. The investigation revealed he “himself was engaged in significant inappropriate conduct in disparaging” coworkers on social media.

Retaliatory termination: McCaleb alleged other employees engaged in similar social media use and the district was “inconsistent in its enforcement of its social media policy.” The summary stated McCaleb wasn’t terminated for a “single inappropriate use of social media,” and the district didn’t claim in his termination letter that his conduct was “inappropriate because of the time of day that he made his posts.”

The summary concluded McCaleb “has not provided additional evidence or arguments which would cause the ICRC to reconsider its decision to administratively close this complaint.”

McCaleb received a “right-to-sue” letter in state district court. The 90-day deadline to sue expired on May 12, 2024, which means he can no longer pursue legal action on the allegations in the complaint.

“Quennel clearly stated his claim to the Iowa Civil Rights Commission, provided a wealth of documentation, and a comprehensive list of witnesses to support his claim. In my professional opinion, the commission should have examined the documentation and spoken to the witnesses instead of dismissing his claim without any investigation,” said Travis Schilling, McCaleb’s attorney, via email.

McCaleb was terminated “for cause,” effective Oct. 18, 2022. The three-page termination letter lists several reasons for his firing, including:

“continued social media posts making disparaging remarks”

replying to a parent’s post about another coach

responding to a parent’s post “alleging a FERPA violation.” The district said it couldn’t provide information about FERPA violations. “This is confidential personnel information under Iowa Code 22.7 (11). The district cannot provide this information.”

failing to show up to supervise a class

posting to Facebook during work hours

McCaleb alleges he supervised the class in question. He said he made Facebook posts during work breaks and kept screenshots of other employees allegedly making Facebook posts during work hours.

“The pattern of conduct you have demonstrated is insubordinate and detrimental to district operations,” the letter stated, among other issues. “You have been given every reasonable opportunity to remedy these concerns and have failed to do so. I recommend to the school board that your employment be immediately terminated . .”

‘. . . treated like we were living in 1930’

According to the complaint, McCaleb began verbally reporting the issues he alleged occurred to school officials. One white coach said, “There are too many Black coaches already,” according to the complaint. A month before he was terminated, during a meeting about his social media posts, McCaleb alleged he asked both the human resources director and acting superintendent how to formally file a grievance, the complaint stated.

McCaleb kept hundreds of pages of screenshots of social media posts, complaints and district letters that he said substantiate his claims of racism, retaliation and discrimination. He painstakingly kept the documentation because, as a Black man, he said his word wouldn’t matter without proof. A dozen community members, including parents and former students, wrote letters of support for McCaleb.

Although he believes there is pervasive racism in the town of 24,591, he wants his job back – and he wants to be a part of making positive changes in the district. An estimated 1,214, or 4.9 percent of Fort Dodge residents are Black.

“I worked too hard for these kids to watch them get treated like we were living in 1930, and we had no rights,” McCaleb said.

He alleged several incidents to support his complaint, including:

He alleged school officials retaliated against his daughter by excluding her from team photos, removing the family from the BAND app and excluding her from a team video. The law firm hired by the district to investigate the claims deemed the complaint of racial discrimination, harassment and bullying to be “unfounded” in an investigation summary report.

But findings from a district investigation stated “potential misconduct” may have violated district policies or expectations as “substantiated,” which included: “Inappropriate jokes and comments about female genitalia and coaches texting and calling players during IHSAA/IGHSAU’s “Family Week.” “The preponderance of the evidence supports that Adams has made inappropriate jokes and comments to the team related to female genitalia, but none were directed at Meah or any specific player on the team.”

Meah McCaleb was hit by a softball in the face, which he said broke four of her braces. McCaleb alleges she received one text from coach Andi Adams, and that wasn’t sufficient for her injuries. According to district findings, Meah wasn’t placed in a “concussion protocol” because she didn’t complain of injury to school officials.

Shortly after he was fired from the district, McCaleb began working for Families First, an outside organization that would have brought him back inside the high school. He alleges the district “banned” him from the high school. The school district told Black Iowa News there were “no public records responsive to this request.”

A year after his termination, McCaleb started Dreamcatcherz Photography and Productionz. He alleges a district athletic director told him that he couldn’t take photos on the football field.

He alleges the N-word was used multiple times in school buildings by school officials and by school staff during a class where McCaleb and another city councilperson were present, and the racial slur was spelled out in school referrals.

McCaleb said another Black coach told him that Porter said he had “white privilege” over him, and McCaleb confronted Porter. The ICRC summary order dated Nov. 1, 2023, stated Porter’s conduct “while inappropriate and unwelcome” didn’t affect McCaleb’s employment.

“Too many families share the same story for it not to be true,” McCaleb said.

‘There’ll be another child of color that experiences the same thing’

Javion Jondle, 18, graduated from Fort Dodge Senior High School in 2023. He earned multiple honors playing football. He also ran track and played basketball, and he hoped sports would be his ticket to college. When college recruiters sought him out, Javion, whose mother is white and father is Black, said a white teammate told him, “The only reason why you’re getting recruited is because you’re Black.”

He alleges that repeated racial hostility from white coaches, teammates, and students harmed his mental health and led him to try to take his own life. His academics suffered. His dreams of playing at a Division 1 school faded.

“It just really messed with my head. I had mental health issues for a while,” Javion said. “I’m just starting to come out of the other side of it.”

Javion and his mother, Andrea Jondle-Howard, said they addressed the alleged issues several times with coaches and school officials and were told it wouldn’t happen again. Even so, what Javion described as escalating incidents plagued him while he played sports at the high school, including:

A white coach called him a “baby back b*tch,” according to Javion.

A white coach “chested up” with him during a conflict on the field, Jondle-Howard said.

A white coach put his arm next to Javion’s and said Javion would receive more scholarship money than him due to his skin color, Javion said.

Students joked about “Black Lives Matter” and George Floyd during a marketing class, which Javion said made him feel uncomfortable.

Jondle-Howard, Javion and McCaleb allege Javion’s grades were illegally shared with a college recruiter. McCaleb alleges he saw the email that was sent to the recruiter. School officials said they can’t comment on the matter. However, findings from a district investigation into a complaint Jondle-Howard filed, shared with Black Iowa News, stated coach Nik Moser committed a “founded” FERPA violation by sending Javion’s school records to Northwestern.

According to the Jan. 27. 2023, summary of the district’s investigation, FERPA requires written parental consent before student educational records may be shared with third parties. The report stated Moser had “verbal permission” to send Javion’s school records but not “written permission.”

“Accordingly, while this appears to be a good faith mistake, a FERPA violation did occur when Coach Moser sent the Northwestern coach JJ’s transcript without written permission from (the) complainant,” stated the district investigative report.

Moser didn’t return repeated calls seeking comment.

Support the Black Iowa Newspaper’s upcoming summer edition with a tax-deductible donation

Javion said the white coaches began to shun him the more he spoke about racial bias.

“It just really hurt me – just to see how cold-hearted they could be,” Javion said.

He said the incidents were “racially motivated.” When he began speaking up about the alleged racial bias he experienced and that he saw happening to his Black coaches, it appeared “he had a target on his back,” his mother said.

“Leadership failed to intervene, follow up, investigate, or address the concerns brought forward,” Jondle-Howard stated in the complaint.

The Jan. 27, 2023, investigative findings referenced 12 incidents the investigator summarized into general allegations, including “inappropriate racial comments,” “recruiting interference/violation of privacy related to school records,” and miscellaneous events.

Those related to discrimination on the basis of race and bullying/harassment were deemed “unfounded” by the investigator.

“The outcome was, of course, not what I was looking for, but it’s documented. It’s on file. There’ll be another child of color that experiences the same thing,” Jondle-Howard said. “And I just think if people continue to document their incidents, at some point, somebody’s got to say, we have a problem here.”

Jondle-Howard shared her son’s story on Facebook, dubbed “Johnny Chronicles.” The series of posts didn’t name her son or others but were a “factual” account of Javion’s “pain” and the “mental abuse” he experienced, she said. Attorney Jerry Schnurr III sent Jondle-Howard a letter on behalf of coach Nik and Katie Moser, alleging defamation.

“I represent Nik and Katie Moser. I have seen a number of your posts on Facebook, which seem to be part of a campaign to discredit and defame Mr. Moser and his family. They, at a minimum, create a false light on Mr. Moser. I do not think it is necessary to go through each post and each defamatory statement you have made,” read the Oct. 18, 2022, letter from the Schnurr Law firm.

The letter asked her to “stop posting at this time about Mr. Moser and his family.”

“It was a scare tactic to shut me up,” Jondle-Howard said.

‘A Black law and a white law:’ Black Fort Dodge residents fight longstanding ‘police harassment’

‘My purpose is to show kids you never fold’

McCaleb was born in Iowa City and has lived in Fort Dodge since he was a child. A former athlete, McCaleb, said he knows the power of sports and would have been a statistic without it. Even so, he struggled academically and initially dropped out of college.

After graduating from Fort Dodge Senior High School, he worked for a while before attending Central College and later Buena Vista University. In 2021, he earned a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and human services, with a minor in psychology.

“The whole purpose of me doing what I did was to show the Black community, and especially my kids, there’s no time limit on how great you can be,” he said. “You may not be able to do it out the gates, but as long as you don’t give up and you put your nose to the ground, you can do whatever you set your mind to.”

Javion said Black coaches are role models who push students and hold them accountable.

“When you talk to a white coach, or you talk to a white person, they automatically think you’re ghetto,” he said. “When you talk to a Black coach, it just makes you feel like you have somebody to talk to. You have somebody to rely on.”

“Without education, who can you be?” McCaleb said. “What’s your future look like? You’re subject to doing what’s the norm for our people trying to get by, by any means necessary.”

The problems in the community, including crime and gun violence, begin at school, he said.

“Why is it we get kicked out of school for the same behaviors but (white students) get repeated chances to prove their worth?” McCaleb said. “They’re just making a paper trail on the Black kids. Which leads them to drop out of school and potentially get into trouble with the law.”

Jondle-Howard said microaggression training should be required at least annually in the school district. She said: “Our white people don’t understand culture change.”

“We live in a white community, and that’s just the way it is,” she said.

Failing to be inclusive is unacceptable, Jondle-Howard, Javion and McCaleb agree.

“There’s got to be some intersectionality discussions with your staff about how to treat people who come from different cultural backgrounds, not just African Americans,” she said. “But you need to allow Black kids to live in their Blackness. And why is that not acceptable?”

McCaleb, who worked in the district as a juvenile court liaison at the high school, alleged he saw repeated instances of white school staff downplaying white students’ wrongdoings but escalating Black students into the criminal justice system.

Javion said the racism he experienced completely changed him. Playing football wasn’t fun anymore. He felt misjudged and ostracized by his white coaches.

“We have Black African Americans in this community that can end up being great — that don’t move forward because of what’s really going on — and nobody gets to see that,” he said.

Now a criminal justice major at Iowa Central Community College, he has a two-year-old son, Legend. The doting young father, who works at a youth shelter, wants to become a juvenile probation officer.

“I’m trying to give back to the kids to show them there is a way out,” he said. “There is a plan that God has set for you.”

Javion is skeptical that Fort Dodge school officials can change. He said they believe stereotypes about Black students and students of color, but offer understanding and help to white students.

“But when it comes to people of color, they don’t do that,” Javion said. “They don’t understand how to do that, and I don’t think they ever will.”

That’s why Black coaches, like McCaleb and the others who still call to check on him, are so important, he said. Black coaches want to see “me happy in life” on and off the field, he said.

“They understand what I went through and understand what I’ve overcome,” Javion said. “So for them to be there and still support me, that’s what real coaches are.”

Despite the controversies and the alleged discrimination he said he experienced, McCaleb knows getting his job back is a long shot. Even so, he wants to advocate for students like Javion and help fix the inequitable systems he said are operating in Fort Dodge schools.

“That’s what I’ve been doing my whole life is working with kids,” he said. “My purpose is to show kids you never fold. At the end of the day, I want change.”

23.11.01-ICRC-Denial-of-Request-for-ReconsiderationDownload

McCaleb-Adams-Investigation-Summary-02259382x7F7E1-1Download

11-23-2022-Complaint-by-Jondle-Andrea-on-behalf-of-Javion-JondleDownload

Final-Investigation-Report.DOCX-1Download

11-23-2022-Complaint-by-Jondle-Andrea-on-behalf-of-Javion-Jondle-1Download

11-23-2022-Timeline-of-Events-Complaint-filed-Javion-Jondle-Andrea-Jondle-HowardDownload

IOWA WRITERS’ COLLABORATIVE